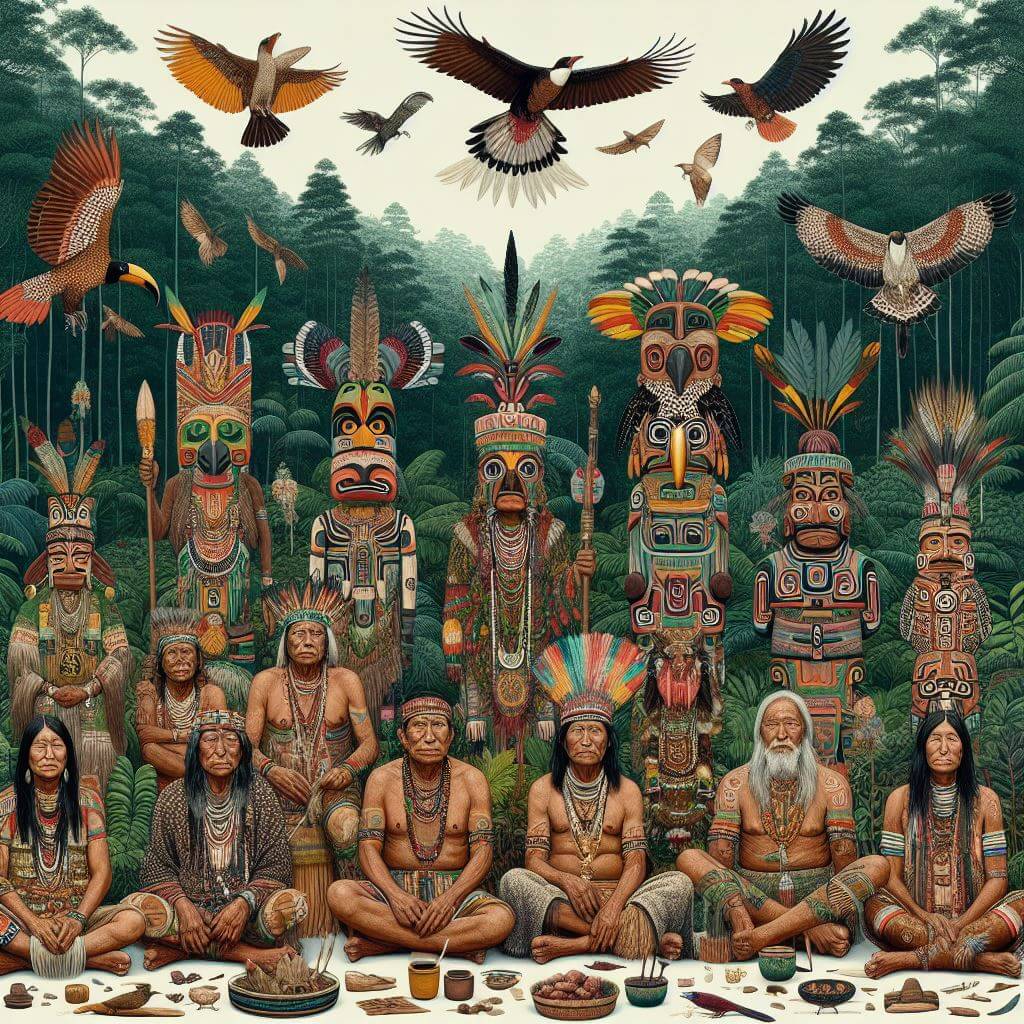

Stewards of nature, indigenous communities around the world have forged a strong bond with forest ecosystems for countless generations. This deep connection goes beyond simply living in these green spaces. For indigenous peoples, forests are not only a habitat; it is the tangled webs of life that contribute to their physical sustenance, spiritual practices, and cultural permanence.

Forests, in their vast biodiversity, provide numerous resources for indigenous communities, including medicinal plants, food and shelter materials, and tools. The wisdom of indigenous peoples, honed over thousands of years, underlies the ecological extraction methods that ensure the longevity of these resources. These traditional practices are based on an understanding of natural cycles and the interdependence of living systems, taught through oral histories and demonstrated in everyday life.

The Importance of Indigenous Knowledge in Nature Conservation

Indigenous communities’ deep knowledge of their local environment is a cornerstone of sustainable practices and conservation efforts. Their understanding is not merely academic; it is a living experience shaped and refined by countless generations of interaction with the natural world. From the deep rainforests of the Amazon to the vast coniferous expanses of Siberia, indigenous peoples have an unparalleled understanding of the intricacies of these ecosystems.

Indigenous knowledge is based on an intrinsic understanding of the many connections within ecosystems. This includes understanding which plants are best for which diseases, when and where to find edible or medicinal resources, and the migration patterns of animal species, which is critical to maintaining ecological balance. A great illustration of this is the controlled burning practiced by many indigenous peoples, which helps prevent larger uncontrolled wildfires, promotes biodiversity, and maintains forest health.

Practices based on indigenous knowledge are the result of holistic philosophies that view people as integral components of the environment, not outsiders. These principles have sometimes been ignored or misunderstood by conventional conservation models, which have tended to view humans as separate from, or even antagonistic to, nature. Rather than maintaining a strict division between human habitation and nature, indigenous conservation practices illustrate how to live as an integral part of the ecosystem.

The value of the knowledge of indigenous peoples goes beyond the purely ecological; it includes strategies for adaptation and resilience in the face of environmental change. For example, many indigenous communities have developed agricultural practices such as agroforestry and permaculture that enrich the soil, conserve water, and provide crop diversity. These sustainable practices provide models that are increasingly relevant as global agriculture looks for ways to adapt to climate change.

The value of the knowledge of indigenous peoples goes beyond the purely ecological; it includes strategies for adaptation and resilience in the face of environmental change. For example, many indigenous communities have developed agricultural practices such as agroforestry and permaculture that enrich the soil, conserve water, and provide crop diversity. These sustainable practices provide models that are increasingly relevant as global agriculture looks for ways to adapt to climate change.

Indigenous knowledge encompasses a cultural richness that values each species and its role in the ecosystem. Celebrations, myths, legends, spiritual practices, and community rules are often linked to the species and natural attractions in their territories. This cultural dimension adds deep responsibility and deeper motivation to manage one’s environment.

The conservation community increasingly recognizes the need to incorporate the knowledge of indigenous peoples and leaders in the development and implementation of conservation strategies. Recognition of ownership and management of traditional lands is critical to protecting biodiversity. Partnership and respect between indigenous groups and conservationists can lead to innovative solutions. These include projects that use traditional knowledge to inform regional planning and sustainable resource management that respects both the ecological needs and cultural traditions of indigenous peoples.

Problems Faced By Indigenous Peoples In Forest Conservation

Despite their undeniable expertise and historical success in forest conservation, indigenous communities face significant challenges that threaten their livelihoods and undermine their role in forest conservation. One of the most serious challenges is the ongoing violation of land rights, which has become a widespread problem for indigenous peoples around the world. For many, the land is more than just a place to live; it is part of their identity, the basis of their culture, and the source of their livelihood. However, this close connection to the land is being disrupted as industries such as logging, mining, agriculture, and even some ill-conceived conservation and development projects are displacing communities, degrading ecosystems, and destroying traditional ways of life.

Legal recognition of indigenous land rights is often inadequate or non-existent, making indigenous territories vulnerable to exploitation. Where rights are recognized, there is often a significant gap between legislation and enforcement. As a result, lands officially under the administration of the indigenous population are being encroached upon without consequences. This can escalate into land conflicts where indigenous communities find themselves up against powerful adversaries, including corporate entities and state forces.

Indigenous environmentalists are often on the front lines, risking their safety to protect their ancestral lands. Unfortunately, these individuals may face persecution, criminalization, violence, or even loss of life. Despite the high stakes, they fight hard to protect their territories, a testament to their deep connection to the land and dedication to conservation. Protecting environmentalists and recognizing their legitimate struggle for their land rights is essential to the progress of forest conservation.

The existential threat posed by climate change adds a layer of complexity to these challenges. Changing weather conditions, increasing the frequency of extreme weather events, and disrupting ecological balance can have devastating consequences for forests and the species that depend on them, including humans. Indigenous communities, whose way of life is precisely adapted to the rhythms of the environment, are particularly vulnerable to these changes. Food sources may become unpredictable, traditional farming methods may be disrupted by changing growing seasons, and water scarcity may become an acute problem.

Climate change may intensify existing struggles. For example, when areas become more susceptible to the effects of climate change, they may be perceived as less desirable for traditional resource extraction and, as a result, may face new threats from speculative land-grabbing or non-traditional methods of resource extraction that may be more efficient. harms the environment.

On a broader social scale, the challenges faced by indigenous peoples intersect with other systemic issues such as poverty, health inequities, and lack of access to education. These complex social issues can limit their ability to actively participate, seek legal ways to protect the land, or even continue traditional practices that contribute to forest conservation.

Ways of Expanding The Opportunities of Indigenous Communities in Forest Conservation

The urgent need to empower indigenous communities in forest conservation requires concerted efforts on various fronts. A multifaceted approach is needed to address the complex range of challenges facing these communities, spanning legal, environmental, social, and economic domains. Indigenous empowerment is not just a matter of justice; it is a strategic and necessary investment in the future health of our planet. There are several ways to facilitate this empowerment and the effective management that comes with it.

One of the important steps is legal and political reform aimed at recognizing and ensuring the land rights of the indigenous population. Land is the foundation on which indigenous peoples’ cultures are built and the foundation on which they can effectively manage and protect forests. Strengthening the legal framework to recognize hereditary ownership of land and ensuring that these laws are respected and enforced at all levels of government is imperative. Clear and legally recognized land tenure rights empower indigenous communities to resist unwanted and harmful exploitation of their lands and allow them to participate in decision-making processes related to land use and conservation.

Political advocacy is key to ensuring these rights and empowering Indigenous voices in the conservation debate. Indigenous leaders and community representatives should be invited to participate in local, national, and international policy development forums. By actively involving indigenous peoples in these dialogues, policymakers can tap into their unique perspectives and knowledge, leading to more effective and inclusive conservation strategies.

There is also a need to raise awareness and education about the critical role indigenous communities play in forest conservation. This can be achieved through mainstream education systems, media, and environmental campaigns that articulate the value of indigenous knowledge and management practices to support biodiversity and ecosystem health. Such awareness-raising initiatives should aim to shift public opinion in support of indigenous peoples’ rights and lead to increased solidarity and partnership between the conservation community and indigenous peoples.

Further empowerment can come from scientific partnerships and collaborations. By combining traditional ecological knowledge with scientific research, we can facilitate innovative conservation approaches that are culturally appropriate and ecologically sound. This collaboration can also offer educational opportunities for indigenous youth, ensuring the transfer of knowledge and skills necessary for effective governance and adaptation to the challenges of the coming decades.

Economic empowerment is another important aspect, particularly through supporting sustainable livelihoods. Indigenous communities often face economic pressures to use their lands irrationally. Thus, creating economic incentives for conservation, such as fees for ecosystem services (PES), can provide financial benefits that will strengthen traditional land management. Similarly, initiatives that promote eco-tourism, sustainable agriculture, and non-timber forest products can help communities thrive while keeping forests intact.

Finally, there is an urgent need to protect the rights and safety of indigenous environmental activists. International and local human rights organizations must work together to monitor and respond to the threats these defenders face. Ensuring their protection and accountability for wrongful actions against them is essential to the ongoing struggle to preserve forests and indigenous peoples’ rights to their lands.