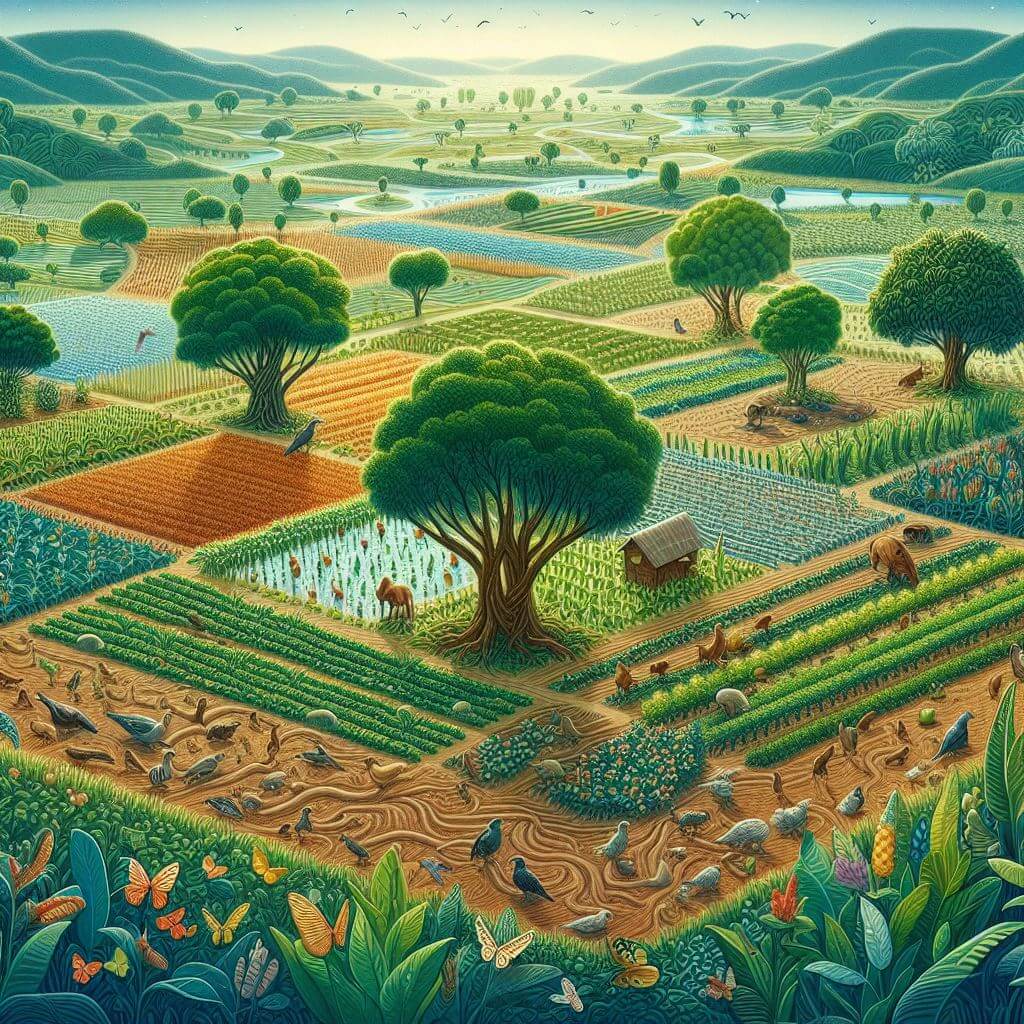

The principles of agroforestry are rooted in an intricate blend of ecological and agricultural knowledge — an approach that acknowledges the many contributions trees make to fertile and sustainable farming systems. The core idea is to harness the natural benefits that trees offer and strategically incorporate them into crop and animal farming practices. These principles are informed by an understanding of ecological interactions and rely on creating a balanced symbiosis between agricultural activities and the natural environment.

Trees play multiple roles within an agricultural context, both directly and indirectly influencing crop production. Their root systems contribute substantially to soil stabilization, drastically reducing erosion by wind and water, vital in preserving topsoil and maintaining land productivity. The architecture of their roots helps to break up compact layers of soil, promoting better water penetration and reducing water runoff, which in turn minimizes the loss of soil and nutrients. The roots are conduits for the deep transport of nutrients as they can access minerals from deeper soil layers and deposit them on the surface via leaf litter, enhancing the availability of nutrients for the crop plants.

Another pillar of agroforestry principles revolves around the beneficial interactions between trees, crops, and livestock. Trees provide necessary shade in agroforestry systems such as silvopasture, which can be a respite for livestock during warm seasons, improving their welfare and productivity. The shade can also protect sensitive crops from excessive sunlight and reduce the moisture loss from the soil, leading to lower irrigation requirements and the preservation of water resources.

Another pillar of agroforestry principles revolves around the beneficial interactions between trees, crops, and livestock. Trees provide necessary shade in agroforestry systems such as silvopasture, which can be a respite for livestock during warm seasons, improving their welfare and productivity. The shade can also protect sensitive crops from excessive sunlight and reduce the moisture loss from the soil, leading to lower irrigation requirements and the preservation of water resources.

Trees also contribute significantly to the carbon cycle, a critical ecological service in the context of global climate change. Their ability to sequester carbon dioxide, an influential greenhouse gas, from the atmosphere is arguably one of their most valuable ecological roles. This carbon is converted into biomass and stored for extended periods, providing a natural way to offset anthropogenic emissions and potentially earning carbon credits for the farmers practicing agroforestry, contributing to the global carbon market.

Diversification of income sources is another fundamental principle. With the integration of trees, farmers are not solely reliant on a single crop or livestock product. The additional tree products, such as fruits, nuts, fodder, timber, and medicinal herbs, foster economic resilience. They can be used for personal consumption, enhancing household nutrition, or sold at different times of the year, providing a more steady income flow throughout the seasons.

Agroforestry rests upon the principle of adaptability and customization. There is no one-size-fits-all model: the types of trees selected, their densities, and the configurations of planting must be tailored to the specific climate, soil, topography, and socioeconomic conditions of a region. This adaptive approach ensures that agroforestry systems can be developed globally, across a wide range of environments and cultural contexts.

Agroforestry Practices

Agroforestry practices represent the varied ways in which trees and shrubs can be combined with crops and/or livestock within agricultural settings, each tailored to address specific ecological and economic goals. These practices are not new; rather, they echo a time-tested symbiotic relationship between farming and forestry, but with modern enhancements. Common agroforestry systems include alley cropping, silvopasture, forest farming, riparian buffers, and home gardens, each with its unique structure and benefits.

Alley cropping is a practice where crops are grown in the spaces between rows of trees or shrubs. This design offers several advantages: the trees can act as windbreaks, reducing wind velocity and protecting crops from damage. The arrangement also allows for sunlight to reach crops while providing a degree of shade to reduce the stress on plants, conserve moisture, and potentially improve yields. The trees in these systems are often nitrogen-fixing species that can enhance soil fertility, or they could be fruit or nut trees that offer additional economic benefits.

Silvopasture is an integration of tree-planting with pasture animals. This combination can yield a diverse set of benefits: trees provide a shelter for the livestock, resulting in increased comfort and potentially better growth rates; the animals, in turn, manage the understory by consuming grasses and weeds, which can minimize the need for mechanical mowing; and the natural cycle of grazing and waste disposal contributes to soil health and nutrient cycling. This system can also increase biodiversity, as the pastoral landscape supports varied habitats.

Forest farming involves the cultivation of shade-tolerant crops within an established or developing forest canopy. This form of agroforestry enables the production of a variety of understory crops, such as medicinal herbs, mushrooms, and decorative foliage, which are valued for their economic and ecological prospects. Forest farming promotes a rich, stable environment that fosters a diverse community of organisms and a layered vegetation structure enhancing resilience against pests and diseases.

Riparian buffers, though often overlooked, are invaluable agroforestry practices that involve planting trees and shrubs along waterways. These vegetated buffers filter sediments and nutrients from farm runoff before they enter the water bodies, protecting aquatic ecosystems and improving water quality. These areas can also serve as wildlife corridors, promoting connectivity between habitats and enhancing biodiversity.

In many parts of the world, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions, home gardens exemplify a traditional and intricate form of agroforestry. These garden systems often combine a diverse array of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants along with livestock, supplying a variety of food products as well as medicines and fodder, reinforcing household food security and income.

Economic and Social Impacts

Agroforestry is not only environmentally sound but also economically sensible. By diversifying farm products, farmers create additional sources of income, which can be particularly important in rural areas where economic opportunities may be limited. Agroforestry systems often require less artificial inputs than conventional monoculture systems, reducing costs and increasing profitability.

On a social level, agroforestry can play a role in community development, providing a shared resource for timber, fruit, and other products that can be economically beneficial for entire communities. It can also be an effective tool in combating food insecurity by increasing the variety and availability of food products.